- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Active involvement in scientific research of persons living with dementia and long-term care users: a systematic review of existing methods with a specific focus on good practices, facilitators and barriers of involvement

BMC Geriatrics volume 24, Article number: 324 (2024)

Abstract

Background

Active involvement of persons living with dementia (PLWD) and long-term care (LTC) users in research is essential but less developed compared to other patient groups. However, their involvement in research is not only important but also feasible. This study aims to provide an overview of methods, facilitators, and barriers for involving PLWD and LTC users in scientific research.

Methods

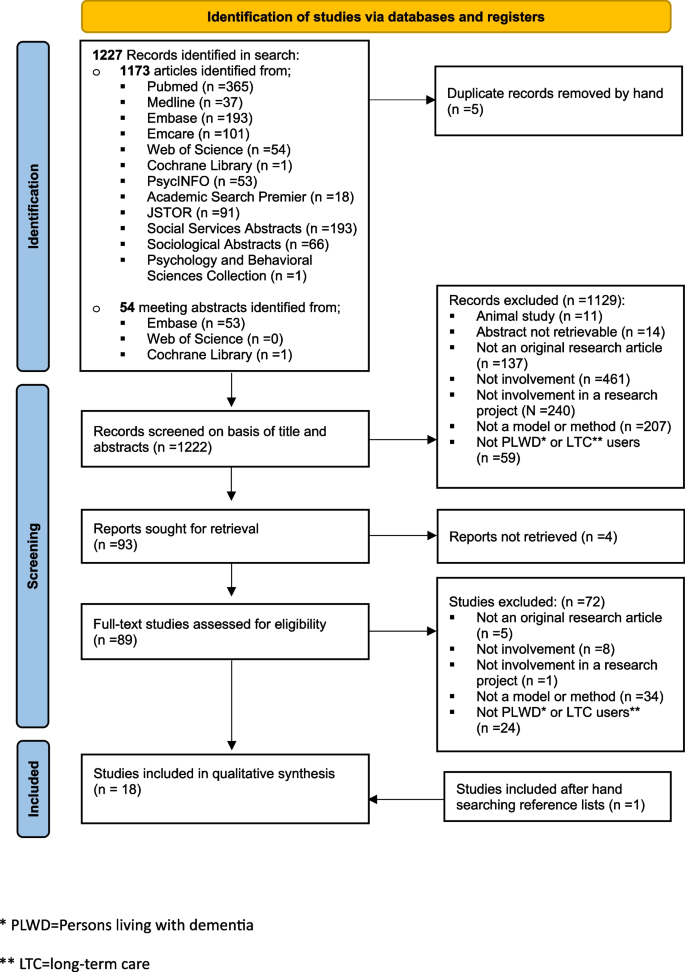

A systematic literature search across 12 databases in December 2020 identified studies involving PLWD, LTC users, or their carers beyond research subjects and describing methods or models for involvement. Qualitative descriptions of involvement methods underwent a risk of bias assessment using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist 2018. A data collection sheet in Microsoft Excel and thematic analysis were used to synthesize the results.

Results

The eighteen included studies delineated five core involvement methods spanning all research phases: advisory groups, formal and informal research team meetings, action groups, workshops, and co-conducting interviews. Additionally, two co-research models with PLWD and carers were found, while only two studies detailed LTC user involvement methods. Four distinct involvement roles were identified: consulting and advisory roles, co-analysts, co-researchers, and partners. The review also addressed barriers, facilitators, and good practices in the preparation, execution, and translation phases of research, emphasizing the importance of diversity, bias reduction, and resource allocation. Trust-building, clear roles, ongoing training, and inclusive support were highlighted.

Conclusions

Planning enough time for active involvement is important to ensure that researchers have time to build a trusting relationship and meet personal needs and preferences of PLWD, LTC users and carers. Researchers are advised not to presume the meaning of burden and to avoid a deficit perspective. A flexible or emergent design could aid involved persons’ ownership of the research process.

Trial registration

Prospero 2021: CRD42021253736.

Background

In research characterized by active involvement, the target group plays a pivotal role in shaping research decisions and outcomes, directly impacting them. Involving patients in health research offers significant benefits [1, 2]: it enhances participant recruitment [2], refines research questions [2], aligns study results with the target population [1, 2], and promotes effective implementation of findings [1]. Active involvement of patients has also benefits for themselves, namely an enhanced understanding of research, building relationships, personal development, improved health and wellbeing, and enjoyment and satisfaction [3, 4]. It gives them a sense of purpose and satisfaction through their tangible impact.

However, for long-term care (LTC) users and persons living with dementia (PLWD) active involvement in research is less developed than for other patient groups [5, 6]. PLWD and LTC users share similar care needs, encompassing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), medication management, medical condition monitoring, and emotional support. Furthermore, a substantial portion of LTC users comprises individuals living with dementia [7]. Additionally, statistical data from the United States reveals that one in four older individuals is likely to reside in long-term care (LTC) facilities [8], and approximately forty to eighty percent of LTC residents in the United States, Japan, Australia, and England experience dementia or severe memory problems [7, 9].

Due to these considerations, we have chosen to combine the target audiences of PLWD and LTC users in our systematic review. However, it's important to note that while there are potential advantages to combining these target groups, there may also be challenges. PLWD and LTC users may have varying needs, preferences, and experiences, including differences in care requirements driven by individual factors like the stage of dementia, coexisting conditions, and personal preferences. Therefore, it's imperative to conduct comprehensive research and involve these communities to ensure that involvement approaches are not only inclusive but also tailored to meet their specific requirements.

Given our ageing population and the intricate health challenges faced by PLWD and LTC users, including their vulnerability and shorter life expectancy in old age, it's crucial to establish effective research involvement methods. These individuals have unique needs and preferences that require attention. They possess a voice, and as researchers, it is our responsibility to not only listen to them but also actively involve them in the research process. Consequently, it is essential to identify means through which the voices of PLWD and LTC users can be effectively heard and ensure that their input is incorporated into research.

Fortunately, publication of studies on involvement of PLWD and LTC users in scientific research is slowly increasing [5, 9,10,11]. A few reviews have described how PLWD and LTC users were involved [5, 9, 10]. However, with the increasing attention for involvement, the understanding of when involvement is meaningful grows and stricter requirements can be imposed to increase the quality of active involvement [12, 13]. To our knowledge there is no up to date overview of involvement methods used with either or both PLWD and LTC users. Such an overview of involvement methods for PWLD and LTC users would provide a valuable, comprehensive resource encompassing various stages of the research cycle and different aspects of involvement. It would equip researchers with the necessary guidance to navigate the complexities of involving PLWD and LTC users in their research projects.

Recognizing the need to enhance the involvement of PLWD and LTC users in scientific research, this systematic review aims to construct a comprehensive overview of the multiple methodologies employed in previous studies, along with an examination of the facilitators and barriers of involvement. Our overarching goal is to promote inclusive and effective involvement practices within the research community. To achieve this objective, this review will address the following questions: (1) What kind of methods are used and how are these methods implemented to facilitate involvement of PLWD and LTC users in scientific research? (2) What are the facilitators and barriers encountered in previous research projects involving PLWD and LTC users?

Methods

Protocol and registration

The search and analysis methods were specified in advance in a protocol. The protocol is registered and published in the PROSPERO database with registration number CRD42021253736. The search and analysis methods are also described below more briefly.

Information sources, search strategy, and eligibility criteria

In preparation of the systematic literature search, key articles and reviews about involvement of PLWD and LTC users in research were screened to identify search terms. In addition, Thesaurus and MeSH terms were used to broaden the search. The search was conducted on December 10, 2020, across multiple databases: PubMed, Medline, Embase, Emcare, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, Academic Search Premier, JSTOR, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection. The search terms were entered in "phrases". The search strategy included synonymous and related terms for dementia, LTC user, involvement, research, method, and long-term care. The full search strategy is provided in supplement 1.

After conducting the search, records underwent initial screening based on titles and abstracts. Selected reports were retrieved for full-text assessment, and studies were evaluated for eligibility based on several criteria. However, no restriction was made regarding publication date. First, to be included studies had to be written in English, German, French, or Dutch. Second, we only included original research studies. Third, studies were excluded when the target group or their representatives were not involved in research, but only participated as research subjects. Fourth, studies were excluded when not describing involvement in research. Therefore, studies concerning involvement in care, policy, or self-help groups were excluded. Fifth, the focus of this systematic review is on methods. Therefore, studies with a main focus on the results, evaluation, ethical issues, and impact of involvement in research were excluded. Additionally, we have not set specific inclusion or exclusion criteria based on study design since our primary focus is on involvement methodologies, regardless of the chosen research design. Sixth, the included studies had to concern the involvement in research of PLWD or adult LTC users, whether living in the community or in institutional settings, as well as informal caregivers or other representatives of these groups who may represent PLWD and LTC users facing limitations. Studies that involved LTC users that were children or ‘young adults’, or their representatives, were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they involved mental healthcare users if it remained unclear if the care that they received entailed more than only treatment from mental healthcare providers, but for example also assistance with ADL.

Terminology

For readability purposes, we use the abbreviation PLWD to refer to persons diagnosed with dementia, and we use the abbreviation LTC users to refer to persons receiving long-term care, at home or as residents living in nursing homes or other residential facilities. We use the term carers to refer to informal caregivers and other representatives of either PLWD or LTC users. As clear and consistent definitions regarding participatory research remains elusive [14, 15], we formulated a broad working definition of involvement in research so as not to exclude any approach to participatory research. We defined involvement in research as “research carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ the target group” [16], where the target group or their representatives take part in the governance or conduct of research and have some degree of ownership of the research [12]. It concerns involvement in research in which lived experienced experts work alongside research teams. We use the terms participation and participants, to refer to people being part of the research as study subjects.

Selection process, data-collection process, and data items

Titles and abstracts were independently screened by the first and second author (JG and LT). Only the studies that both reviewers agreed and met the inclusion criteria were included in the full-text screening process. Any uncertainty about whether the studies truly described a model or approach for involvement, was resolved by a quick screening of the full-text paper. The full-text screening process was then conducted according to the same procedure by JG and LT. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. If no agreement could be reached, a third researcher (MC) was consulted. References of the included studies were screened for any missing papers.

The following information was collected on a data collection sheet in Microsoft Excel: year and country of publication, topic, research aim, study design, living situation of involved persons (at home or institutionalized), description of involved persons, study participants (study subjects), theories and methods used, type/role(s) of involvement, research phase(s), recruitment, consent approach, study setting, structure of participatory activities, training, resources, facilitators, barriers, ethics, benefits, impact, and definition of involvement used.

JG independently extracted data from all included studies, the involved co-researcher (THL) independently extracted data from two studies, the second author (LT) from five. Differences in the analysis were discussed with the co-researcher (THL) and second author (LT) until consensus was reached. As only minor differences emerged, limited to the facilitator and barrier categories, data from the remaining studies was extracted by JG.

Risk of bias assessment

Every research article identified through the systematic review exclusively comprised qualitative descriptions of the involvement method(s) employed. Consequently, all articles underwent evaluation using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist 2018 [17], as opposed to the checklists intended for quantitative or mixed methods research. All included studies were independently assessed on quality by two reviewers (JG,LT) and any disagreement was resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. The CASP Qualitative Checklist consists of ten questions. The checklist does not provide suggestions on scoring, the first author designed a scoring system: zero points if no description was provided (‘no’), one point if a minimal description was provided (‘can’t tell’) and two points when the question was answered sufficiently (‘yes’). The second question of the checklist, “is a qualitative methodology appropriate”, was not applicable to the aims (i.e., to describe involvement) of the included studies and was therefore excluded. The tenth question was translated into a ‘yes’, ‘can’t tell’, or ‘no’ score to fit the scoring system. A maximum of eighteen points could be assigned.

Synthesis methods

Tables were used to summarize the findings and to acquire an overview of (1) the kinds of methods used to enable involvement of PLWD, LTC users, or carers in scientific research, and (2) the facilitators and barriers for involving this target group in scientific research. As to the first research aim, the headings of the first two tables are based on the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public, long form version 2 (GRIPP2-LF) [18]. Because our systematic review focusses on methods, only the topics belonging to sections two, three, and four were included. Following Shippee et al., three main research phases were distinguished: preparation, execution, and translation [19]. Furthermore, the following fields were added to the GRIPP2-LF: First author, year of publication, country of study, setting of involvement, frequency of meetings, and a summary description of activities.

Concerning the second research aim, the extracted facilitators, barriers, and good practices were imported per study in ATLAS.ti for qualitative data analysis. Following the method for thematic synthesis of qualitative studies in systematic reviews [20], all imported barriers, facilitators and good practices were inductively coded staying 'close' to the results of the original studies, which resulted in 50 initial codes. After multiple rounds of pile sorting [21], based on similarities and differences and discussions in the research team, this long code list was grouped into a total of 27 categories, which were thereafter subsequently organized into 14 descriptive themes within the three research phases (preparation, execution, translation).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The Prisma Flow Diagram was used to summarize the study selection process [22]. In the full text screening, 72 of the 93 remaining studies were excluded because they were not original research articles (n = 5), not about involvement (n = 8), not about involvement in a research project (n = 1), they did not describe a model or method for involvement (n = 34), or they were not about PLWD or LTC users (n = 24). The search resulted in 18 publications eligible for analysis (Fig. 1).

Table 1 presents the general study characteristics. Two studies explicitly aimed to develop a model for involvement or good practice, and both focus on co-research either with PLWD [23] or their carers [13]. The other sixteen provide a description of the involvement of PLWD [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] or LTC users in their research projects [35,36,37,38,39].

Quality assessment

Table 1 presents the CASP-score per study [17]. Five scored 16 to 18 points [13, 28, 29, 32, 35], indicating high quality with robust methods, clear aims, and strong data analysis. Eleven scored 12 to 15 [23, 24, 26, 30, 32,33,34, 36,37,38,39], showing generally strong methodologies but with some limitations. Two scored 9 or lower [25, 27], signifying significant methodological and analytical shortcomings. Notably, these low-scoring studies were short articles lacking clear recommendations for involvement in research.

Design and implementation of involvement

Phases and methods of involvement

Table 2 describes the involvement methods used for and the implementation of involvement in research. The included studies jointly presented methods for involvement in the three main research phases [19]. Regarding the preparation phase, which involves the preparatory work for the study, only three studies provided detailed descriptions of the methods employed [26, 30, 32]. The execution phase, encompassing the actual conduct of the research, was most frequently discussed [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Five studies addressed the translation phase [13, 25, 31, 36, 37], where the focus shifts to translating research findings into actionable outcomes.

The eighteen studies introduced a variety of involvement methods, categorizable into five groups: 1) advisory groups, 2) research team meetings (both formal and informal), 3) action groups, 4) workshops, and 5) co-research in interviews. In five studies, individuals including PLWD, LTCF residents, carers, and health professionals participated in advisory/reference groups [25,26,27, 32], working groups [27], and panels [28]. These groups offered valuable feedback on research aspects, spanning protocols, design, questionnaires, and implementation of research. Meetings occurred at varying frequencies - monthly, quarterly, or biannually.

Two studies exemplify diverse research collaboration settings. One involving older individuals within an academic research team of five [37], and another featuring a doctoral student and a co-researcher conducting informal monthly discussions at a local coffee shop [31]. Brown et al. sought to minimize power differentials and enhance inclusivity [37], while Mann and Hung focused on benefiting people with dementia and challenging negative discourse on dementia [31].

An additional five studies employed methods involving frequent meetings, including action [35, 39], inquiry [23], and discussion groups [29, 36] In these groups, involved persons with lived experience contributed to developing a shared vision and community improvements, such as enhancing the mealtime experience in care facilities [35].

Seven studies involved individuals through workshops, often conducted over one or two sessions. These workshops contributed to generating recommendations [37], informing future e-health designs [29, 30], and ensuring diverse perspectives and lived experiences were included in data analysis [13, 24, 32, 33]. In three studies, representatives worked as co-researchers in interviews, drawing on personal experiences to enhance the interview process, making it more dementia-appropriate and enriching data collection [13, 32, 34]. Finally, one study involved representatives in the recruitment and conduct of interviews [38].

People involved

The number of persons involved varied from a single co-researcher [31] to 34 panel individuals providing feedback on their experiences in a clinical trial [28]. Thirteen studies focussed on PLWD: eleven involved PLWD themselves [23,24,25,26,27, 29,30,31,32,33,34], one exclusively focused on caregivers [13], and another one involved people without or with mild cognitive impairment, who participated in a study examining the risks of developing Alzheimer's disease [28]. Although not all articles provided descriptions of the dementia stage, available information indicated that individuals involved typically fell within the early to mid-stages of dementia [29, 30, 32,33,34]. Next to PLWD and carers, two studies additionally involved organizational or advocacy representatives [25, 27]. The other five studies concerned older adults living in a LTC facility. Two of them involved older residents themselves [35, 39], the other three carers, older community/client representatives or health care practitioners [36,37,38].

Roles and level of involvement

Four general roles could be identified. First, consultation and advisory roles were held by PLWD and carers [25,26,27,28,29,30, 32], where involved persons share knowledge and experiences to make suggestions [32], but the research team retained formal decision-making power [25]. Second, PLWD were involved as co-analysts in data analysis [24, 32, 33]. Co-analysts influence data analysis, but the decision-making power remained with academic researchers [24]. Third, in six studies the co-researcher role was part of the research design in which involved persons and researchers steer and conduct research together [13, 23, 31, 32, 34, 36]. Finally, two studies partnered with LTC residents [35, 39], with residents at the core of the group, and positioned as experts by experience [39]. Residents had the decision-making authority regarding how to improve life in LTC facilities [35].

Models for involvement in research

Only two studies designed a model for co-research with PLWD [23] or their carers [13] across all research phases. These models underscored the importance of iterative training for co-researchers [13, 23] and academic researchers [23]. Furthermore, these studies advocate involving co-researchers early on in the research process [13] and in steering committees [23]. Co-researchers can be involved in designing research materials [23], conducting interviews [13, 23], analysing data [13], and co-disseminating findings [13, 23]. Additionally, one study stressed involving PLWD in identifying (future) research priorities [23].

Barriers, facilitators, and good practices in research phases

Preparation phase

Table 3 describes the barriers, facilitators, and good practices per main research phase. Lack of diversity in ethnicity and stages of dementia in the recruitment of involved persons is mentioned as a recurring barrier [26, 28, 32, 33]. The exclusion of people with cognitive impairments is partly due to gatekeepers’ and recruiters’ bias towards cognitively healthy people [28, 32]. It is stressed that researchers should refrain from making assumptions about the abilities of PLWD and ask the person what he/she is willing to do [31]. It is considered good practice to involve people regardless of cognitive abilities [23], based on skills, various personal characteristics [13] and, if possible, relevant prior experience [38].

Many studies stress the importance of building a mutual trusting relationship between involved persons and academic researchers [13, 23, 31, 33, 34, 37]. A good relationship is believed to break down social barriers [37], foster freedom of expression [33], and thereby avoiding tokenistic involvement [13]. In addition, spending time with these persons is important to become familiar with an individual’s strengths and limitations [31].

Opting for naturally evolving involvement roles was mentioned as a barrier, as this may result in conflicting expectations and irrelevant tasks [37]. A clear role description and clarification of tasks is key to balancing potentially different expectations of the involved persons and researchers [26, 28, 29, 32, 38]. When designing a role for involvement in research, good practices dictate taking into account personal skills, preferences, development goals, and motivation for involvement [13, 32]. This role should ideally be designed in collaboration with involved persons [13, 32].

The perception of providing training to involved persons is ambivalent. Studies cited that training should not aim to transform them into “pseudo-scientist” [32, 37] and that it raises the costs for involvement [28]. However, multiple scholars emphasize the importance of providing iterative training to facilitate meaningful involvement and development opportunities [13, 23, 28, 31,32,33, 36, 37]. Training can empower involved persons to engage in the research process equally and with confidence, with the skills to fulfil their role [13, 33, 38]. However, the implementation of training may present a potential conflict with the fundamental principle of valuing experiential knowledge [37] and should avoid the objective of transforming co-researchers into 'expert' researchers [32]. Academic researchers should also be offered training on how to facilitate meaningful involvement [13, 23, 28, 31].

Limited time and resources were mentioned as barriers to involvement that can delay the research process [13, 33, 36, 39], restrict the involvement [28] and hinder the implementation of developed ideas [39]. Financial compensation for involvement is encouraged [25,26,27, 32], as it acknowledges the contribution of involved persons [13]. Thus, meaningful involvement in research requires adequate funding and infrastructure to support the involvement activities [13, 28, 33, 37].

Execution phase

The use of academic jargon and rapid paced discussions [13, 37], power differentials, and the dominant discourse in biomedical research on what is considered “good science” can limit the impact of involvement [13, 24, 32, 36, 37]. Facilitating researchers should reflect on power differentials [35] and how decision-making power is shared [31]. Other facilitating factors are making a glossary of terms used and planning separate meetings for “technical topics” [37]. In addition, an emergent research design [35] or a design with flexible elements [28] can increase ownership in the research project and provide space for involvement to inform the research agenda [28, 35]. This requires academic researchers to value experiential knowledge and to have an open mind towards the evolving research process [13, 23, 31].

Furthermore, managing the involvement process and ensuring equity in the collaboration [13, 32, 33], facilitating researchers must encourage involved persons to voice their perspectives. This means that they sometimes need to be convinced that they are experts of lived experience [32, 33, 36, 37, 39]. To enable involvement of PLWD, the use of visual and creative tools to prompt memories can be considered [24, 30, 33, 34], as well as flexibility in relation to time frames and planning regular breaks to avoid too fast a pace for people who may tire easily [24, 25, 29, 30].

Involvement can be experienced as stressful [13, 32, 38] and caring responsibilities may interfere [26]. Tailored [29] physical and emotional support should therefore be offered [13, 23, 38] without making assumptions about the meaning of burden [30, 31]. Moreover, being the only PLWD involved in an advisory group was experienced as intimidating [25] and, ideally, a larger team of PLWD is involved to mitigate responsibilities [37]. PLWD having a focal point of contact [28, 37] and involving nurses or other staff with experience working with PLWD and their carers [29, 30] are mentioned as being beneficial. Some stress the importance of involving carers when engaging with PLWD in research [25, 29, 30].

To avoid an overload of information that is shared with the involved persons, tailoring information-sharing formats to individual preferences and abilities is essential to make communication effective [27, 37].

Translation

Two studies indicated a need for more robust evaluation measures to assess the effect of involvement [28, 33]. Reflection and evaluation of the involvement serves to improve the collaboration and to foster introspective learning [13, 23, 26, 31]. The included studies evaluated involvement through the use of reflective diaries [13] or a template [38] with open-ended questions [33].

Two studies postulate that findings should benefit and be accessible to PLWD [23, 31]. The use of creative tools not only enables involvement of PLWD, but can also increase accessibility of research findings and expand the present representation of PLWD [23].

Discussion

The 18 included studies presented multiple methods for involvement in all three research phases. We found five types of involvement: advisory groups, (formal and informal) research team meetings, action groups, workshops, and co-conducting interviews. Only two studies described methods for involvement of LTC users in research. Involved persons were most often involved in consulting and advisory roles, but also as co-analysts, co-researchers, and partners. Involved persons’ roles can evolve and change over time. Especially as involved persons grow into their role, and gain confidence and knowledge of the specific research project, a more active role with shared responsibilities can become part of the research project. In addition, multiple involvement roles can be used throughout the research depending on the research phase.

Compared to the five types of involvement that we identified, other literature reviews about involvement methods for LTC users and PLWD in research also described advisory groups [10] and workshops [5, 11], and methods that were similar to research team meetings (drop-in sessions and meetings [11]). Methods for action research (action groups) and co-conducting research (interviews) were not included by these other review studies. In addition to our findings, these other reviews also described as involvement methods interviews and focus groups [5, 10] surveys [10], reader consultation [11]. Those types of methods were excluded from our study, because our definition of involvement is more strict; collecting opinions is not involvement per se, but sometimes only study participation. Moreover, compared to these previous reviews we set a high standard for transparency about the participation methods and the level of detail at which they are described.

Engaging the target group in research, particularly when collaborating with PLWD, LTC users, and carers, involves navigating unforeseen challenges [40]. This requires academic researchers to carefully balance academic research goals and expectations, and the expectations, personal circumstances and development goals related to the involved person. The aim is to maximize involvement while being attentive to the individual’s needs and avoiding a deficit perspective. Effective communication should be established, promoting respect, equality, and regular feedback between all stakeholders, including individuals living with dementia and LTCF staff. Building a mutual trusting relationship between involved persons and academic researchers through social interaction and clear communication is key to overcome barriers and ensure meaningful involvement. Inclusivity and empowerment, along with fostering an environment where diverse voices are heard, are crucial for the success of involvement in research. Our results are in line with a recent study concerning the experiences of frail older persons with involvement in research, confirming the importance of avoiding stereotypic views of ageing and frailty, building a trusting relationship, and being sensitive to older persons’ preferences and needs [41].

Furthermore, our results show that training academic researchers and involved persons is essential to develop the skills to facilitate involvement and to fulfil their role with confidence, respectively. Whilst the need for training is acknowledged by others [41, 42], there are legitimate objections to the idea of training involved persons, as the professionalization underpinning the concept of training is at odds with voicing a lay perspective [43, 44]. Furthermore, it is argued that experiential knowledge is compromised when training is structured according to the dominant professional epistemology of objectivity [45]. Therefore, training of involved persons should not focus on what researchers think they ought to know, but on what they want to learn [41].

Academic culture was frequently mentioned as a barrier to meaningful involvement. This result resonates with the wider debate related to involvement in health research which is concerned about active or “authentic involvement” being replaced with the appropriation of the patient voice as an add-on to conventional research designs [12, 46]. It is argued that such tokenistic involvement limits the involved persons’ ability to shape research outcomes [46]. To reduce tokenism requires a culture shift [13]. We believe that due to the strict definition of involvement and high transparency standard used in this review, tokenistic approaches were excluded. This may set an example for how to stimulate making this culture shift.

Furthermore, the importance of practical aspects such as funding and, by extension, the availability of time should not be underestimated. Adequate funding is necessary for compensation of involvement, but also to ensure that researchers have ample time to plan involvement activities and provide personalized support for PLWD, LTC residents and their carers. Funding bodies increasingly require involvement of the public to be part of research proposals. Yet, support in terms of financial compensation and time for the implementation of involvement in research is rarely part of funding grants [42]. In addition, whereas an emergent design could aid the impact of involvement, funders often require a pre-set research proposal in which individual components are already fixed [5, 47]. This indicates that not only do academic researchers and culture need to change, academic systems also need to be modified in order to facilitate and nurture meaningful involvement [47].

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this review is the inclusion of over ten scientific databases, with a reach beyond the conventional biomedical science databases often consulted in systematic reviews. Besides, we believe that we have overcome the inconsistent use of terminology of involvement in research by including also other terms used, such as participation and engagement, in our search strategy. However, there was also inconsistency in length of publications and precision of the explanation of the process of involvement. E.g., involvement in the execution phase was often elaborated on, contributions to the research proposal and co-authoring research findings were only stated and not described. This presented challenges for data extraction and analysis, as it was not always possible to identify how the target group was involved. Involvement in these research phases is therefore not fully represented in this review.

The included studies in this review, the majority of which are of high quality, provide methods for involvement of PLWD and LTC users in research and they do not explicitly attend to the effectiveness or impact of the method for involvement used. Therefore, a limitation of this review is that it cannot make any statements regarding the effectiveness of the involvement methods included. Moreover, our target population was broad, although PLWD and LTC users are largely overlapping in their care needs and share important features, this may have led to heterogeneous results. In future research, it would be interesting to interpret potential differences between involvement of PLWD, LTC users, and their carers. However, as we expected, the amount of literature included in our analyses was too limited to do so. Furthermore, whereas the broad target group is a limitation it is also a strength of our review. Limiting our search to specifically persons living in LTC facilities would have provided limited methods for involvement of persons living with dementia. Our broad target groups enabled us to learn from research projects in which people living with early staged dementia are directly involved from which we can draw lessons on the involvement of people with more advanced stages of dementia and persons living with cognitive problems who live within LTC facilities.

Since January 2021 quite some research has been published about the importance of involvement in research. Although we had quickly screened for new methods, we realise that we may have missed some involvement methods in the past years. There will be a need for a search update in the future.

Implications for future research

Our review shows that a flexible and emergent design may help to increase involved persons' influence on and ownership in the research process. However, not all research objectives may be suitable for the implementation of an emergent design. Future research should therefore examine how aspects of a flexible emergent design can be integrated in, e.g., clinical research without compromising the validity of research outcomes.

Alzheimer Europe has called for the direct involvement of persons living with dementia in research [48]. In addition, Swarbrick et al. (this review) advise to involve persons regardless of their cognitive abilities [23]. These statements question the involvement of proxies, such as carers, professional caregivers and others involved in the care of PLWD. While PLWD and persons with other cognitive problems constitute a significant group within residential and nursing homes [7], none of the studies included in this review have provided methods to directly involve persons with more advanced stages of dementia. This raises the question if research methods should be adapted to allow those with more advanced stages of dementia to be involved themselves or if, concerning the progressive nature of the disease, it is more appropriate to involve proxies. And secondly who should these proxies be? Those that care for and live with persons with an advanced stage of dementia, or for example a person living with an early stage of dementia to represent the voices of persons with more advanced stages of dementia [31]?

Future research should adopt our example for stricter requirements for involvement and transparency about the involvement methods used. This will reduce tokenistic involvement and further promote the culture shift towards meaningful involvement. In addition, future research should assess the impact of the involvement methods that are described in this review. One of the first instruments that that may be used to do so in varying healthcare settings is the Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool (PPEET) [49]. Moreover, scholars in this review stress, and we agree with this, that future research is needed on the involvement of persons with more advanced stages of dementia to ensure their voices are not excluded from research [33, 34].

Conclusions

This review provides an overview of the existing methods used to actively involve PLWD, LTC users, and carers in scientific research. Our findings show that their involvement is feasible throughout all research phases. We have identified five different methods for involvement, four different roles, and two models for co-research. Our results suggest that planning enough time for involving PLWD, LTC users, and carers in research, is important to ensure that researchers have time to build a trusting relationship and meet their personal needs and preferences. In addition, researchers are advised not to presume the meaning of burden and to avoid a deficit perspective. A flexible or emergent design could aid involved persons’ ownership in the research process.

Availability of data and materials

The full search strategy is provided in supplement 1. The data extraction form can be provided by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CASP:

-

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

- GRIPP2-LF:

-

Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public, long form version 2

- LTC:

-

Long-term care

- PLWD:

-

Persons living with dementia

References

Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-89.

Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2014;7(4):387–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0065-0.

Staley K. Exploring impact: Public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. 2009. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Involve_Exploring_Impactfinal28.10.09.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024

Ashcroft J, Wykes T, Taylor J, et al. Impact on the individual: what do patients and carers gain, lose and expect from being involved in research? J Ment Health. 2016;25(1):28–35. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1101424.

Backhouse T, Kenkmann A, Lane K, et al. Older care-home residents as collaborators or advisors in research: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):337–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv201.

Bendien E, Groot B, Abma T. Circles of impacts within and beyond participatory action research with older people. Ageing Soc 2020:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001336.

Lepore MED, Meyer J, Igarashi A. How long-term care quality assurance measures address dementia in Australia, England, Japan, and the United States. Ageing Health Res 2021;1(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahr.2021.100013.

Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Disability and care needs among older Americans. Milbank Q. 2014;92(3):509–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12076.

Bethell J, Commisso E, Rostad HM, et al. Patient engagement in research related to dementia: a scoping review. Dementia. 2018;17(8):944–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218789292.

Miah J, Dawes P, Edwards S, et al. Patient and public involvement in dementia research in the European Union: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1217-9.

Schilling I, Gerhardus A. Methods for involving older people in health research—a review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(12):1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121476.

Andersson N. Participatory research—A modernizing science for primary health care. J Gen Fam Med. 2018;19(5):154–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgf2.187.

Di Lorito C, Godfrey M, Dunlop M, et al. Adding to the knowledge on patient and public involvement: reflections from an experience of co-research with carers of people with dementia. Health Expect. 2020;23(3):691–706. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13049.

Islam S, Small N. An annotated and critical glossary of the terminology of inclusion in healthcare and health research. Res Involve Engage. 2020;6(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00186-6.

Rose D. Patient and public involvement in health research: Ethical imperative and/or radical challenge? J Health Psychol. 2014;19(1):149–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313500249.

NIHR. Briefing notes for researchers: public involvement in NHS, health and social care research. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/briefing-notes-for-researchers-public-involvement-in-nhs-health-and-social-care-research/27371#Involvement. Accessed 12 Jan 2023.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2018. https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2023.

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-017-0062-2.

Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1151–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12090.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Saldana JM. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: SAGE Publications; 2015.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, The PRISMA, et al. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021:372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Swarbrick C, Doors O, et al. Developing the co-researcher involvement and engagement in dementia model (COINED): A co-operative inquiry. In: Keady J, Hydén L-C, Johnson A, et al., editors. Social research methods in dementia studies: Inclusion and innovation. New York, Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group; 2018. p. 8–19.

Clarke CL, Wilkinson H, Watson J, et al. A seat around the table: participatory data analysis with people living with dementia. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(9):1421–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318774768.

Flavin T, Sinclair C. Reflections on involving people living with dementia in research in the Australian context. Australas J Ageing. 2019;38(Suppl 2):6–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12596.

Giebel C, Roe B, Hodgson A, et al. Effective public involvement in the HoST-D programme for dementia home care support: From proposal and design to methods of data collection (innovative practice). Dementia (London). 2019;18(7–8):3173–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301216687698.

Goeman DP, Corlis M, Swaffer K, et al. Partnering with people with dementia and their care partners, aged care service experts, policymakers and academics: a co-design process. Australas J Ageing. 2019;38(Suppl 2):53–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12635.

Gregory S, Bunnik EM, Callado AB, et al. Involving research participants in a pan-European research initiative: the EPAD participant panel experience. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00236-z.

Hanson E, Magnusson L, Arvidsson H, et al. Working together with persons with early stage dementia and their family members to design a user-friendly technology-based support service. Dementia. 2007;6(3):411–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301207081572.

Hassan L, Swarbrick C, Sanders C, et al. Tea, talk and technology: patient and public involvement to improve connected health “wearables” research in dementia. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-017-0063-1.

Mann J, Hung L. Co-research with people living with dementia for change. Action Research. 2019;17(4):573–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750318787005.

Poland F, Charlesworth G, Leung P, et al. Embedding patient and public involvement: managing tacit and explicit expectations. Health Expect. 2019;22(6):1231–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12952.

Stevenson M, Taylor BJ. Involving individuals with dementia as co-researchers in analysis of findings from a qualitative study. Dementia (London). 2019;18(2):701–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217690904.

Tanner D. Co-research with older people with dementia: experience and reflections. J Ment Health. 2012;21(3):296–306. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.651658.

Baur V, Abma T. “The Taste Buddies”: participation and empowerment in a residential home for older people. Ageing Soc. 2012;32(6):1055–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X11000766.

Beukema L, Valkenburg B. Demand-driven elderly care in the Netherlands. Action Research. 2007;5(2):161–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750307077316.

Brown LJE, Dickinson T, Smith S, et al. Openness, inclusion and transparency in the practice of public involvement in research: a reflective exercise to develop best practice recommendations. Health Expect. 2018;21(2):441–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12609.

Froggatt K, Goodman C, Morbey H, et al. Public involvement in research within care homes: benefits and challenges in the APPROACH study. Health Expect. 2016;19(6):1336–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12431.

Shura R, Siders RA, Dannefer D. Culture change in long-term care: participatory action research and the role of the resident. Gerontologist. 2011;51(2):212–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq099.

Cook T. Participatory research: Its meaning and messiness. Beleidsonderzoek Online. 2020;3:1–21. https://doi.org/10.5553/BO/221335502021000003001.

Haak M, Ivanoff S, Barenfeld E, et al. Research as an essentiality beyond one’s own competence: an interview study on frail older people’s view of research. Res Involv Engage. 2021;7(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-021-00333-7.

Chamberlain SA, Gruneir A, Keefe JM, et al. Evolving partnerships: engagement methods in an established health services research team. Res Involve Engage. 2021;7(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-021-00314-w.

Bélisle-Pipon J-C, Rouleau G, Birko S. Early-career researchers’ views on ethical dimensions of patient engagement in research. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0260-y.

Ives J, Damery S, Redwod S. PPI, paradoxes and Plato: who’s sailing the ship? J Med Ethics. 2013;39(3):181–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2011-100150.

De Graaff M, Stoopendaal A, Leistikow I. Transforming clients into experts-by-experience: a pilot in client participation in Dutch long-term elderly care homes inspectorate supervision. Health Policy. 2019;123(3):275–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.11.006.

Cook T. Where Participatory Approaches Meet Pragmatism in Funded (Health) Research: The Challenge of Finding Meaningful Spaces. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2012;13(1). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1783.

Paylor J, McKevitt C. The possibilities and limits of “co-producing” research. Front Sociol. 2019;4:23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00023.

Gove D, Diaz-Ponce A, Georges J, et al. Alzheimer Europe’s position on involving people with dementia in research through PPI (patient and public involvement). Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(6):723–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1317334.

Abelson J, Li K, Wilson G, et al. Supporting quality public and patient engagement in health system organizations: development and usability testing of the Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool. Health Expect. 2016;19(4):817–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12378.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jan W. Schoones, information specialist Directorate of Research Policy (formerly: Walaeus Library, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, the Netherlands), for helping with the search.

Funding

This systematic review received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept: HD, LT, MC, WA; design of study protocol: JG, LT, MC; data collection and extraction: JG, LT, MC, THL; data analysis and interpretation: all authors; writing, editing and final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

There are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Groothuijse, J.M., van Tol, L.S., Leeuwen, C.C.M.(.Hv. et al. Active involvement in scientific research of persons living with dementia and long-term care users: a systematic review of existing methods with a specific focus on good practices, facilitators and barriers of involvement. BMC Geriatr 24, 324 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04877-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04877-7