- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Acceptability, values, and preferences of older people for chronic low back pain management; a qualitative evidence synthesis

BMC Geriatrics volume 24, Article number: 24 (2024)

Abstract

Background

Chronic primary low back pain (CPLBP) and other musculoskeletal conditions represent a sizable attribution to the global burden of disability, with rates greatest in older age. There are multiple and varied interventions for CPLBP, delivered by a wide range of health and care workers. However, it is not known if these are acceptable to or align with the values and preferences of care recipients. The objective of this synthesis was to understand the key factors influencing the acceptability of, and values and preferences for, interventions/care for CPLBP from the perspective of people over 60 and their caregivers.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL and OpenAlex, for eligible studies from inception until April 2022. We included studies that used qualitative methods for data collection and analysis; explored the perceptions and experiences of older people and their caregivers about interventions to treat CPLBP; from any setting globally. We conducted a best fit framework synthesis using a framework developed specifically for this review. We assessed our certainty in the findings using GRADE-CERQual.

Results

All 22 included studies represented older people’s experiences and had representation across a range of geographies and economic contexts. No studies were identified on caregivers. Older people living with CPLBP express values and preferences for their care that relate to therapeutic encounters and the importance of therapeutic alliance, irrespective of the type of treatment, choice of intervention, and intervention delivery modalities. Older people with CPLBP value therapeutic encounters that validate, legitimise, and respect their pain experience, consider their context holistically, prioritise their needs and preferences, adopt a person-centred and tailored approach to care, and are supported by interprofessional communication. Older people valued care that provided benefit to them, included interventions beyond analgesic medicines alone and was financially and geographically accessible.

Conclusions

These findings provide critical context to the implementation of clinical guidelines into practice, particularly related to how care providers interact with older people and how components of care are delivered, their location and their cost. Further research is needed focusing on low- and middle-income settings, vulnerable populations, and caregivers.

Background

Low back pain (LBP) and other musculoskeletal conditions represent a sizable contribution to the global burden of disability [1,2,3,4,5]. While the prevalence and impact of LBP are relevant across the life-course, global estimates for prevalence and disability show rates to be greatest in older age. The high prevalence of LBP in older people accounts for frequent care seeking for LBP [6], particularly among older adults experiencing recurrent LBP [7]. The number of older people experiencing and seeking care for LBP is expected to increase due to population ageing and an increasing prevalence of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases [8]. Despite this, intervention trials and clinical guidelines for LBP disproportionately underrepresent older people [9, 10], potentially leaving an important knowledge gap for optimal care of LBP in older people.

Clinical management of LBP is characterized by multiple and varied interventions, delivered by a wide range of health and care workers [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. In many contexts the interventions delivered may not be aligned with best evidence leading to unwarranted care variation and potential harm. Further, interventions may not be aligned with the values, preferences and acceptability attitudes among care recipients (and/or their carers), substantiating the need for global guidelines in this area [21]. Importantly, values and preferences of older people likely differ to younger adults. From the perspective of healthy ageing, carers are an essential workforce for supporting functional ability in older people and enabling ageing in place. The perspectives of carers are therefore critical to ensure care planning and delivery for any health condition experienced by an older people is feasible and acceptable and does not negatively impact on the quality of life of the carer [22, 23] . For example, recent work has also identified the need to sample perspectives of carers related to delivery of care for people living with chronic pain [24].

In response to this context and the priority to support healthy ageing, the World Health Organization (WHO) initiated the development of standard clinical guideline for the non-surgical management of chronic primary LBP (CPLBP) in adults, including older people, in primary and community care settings in 2020 [21]. The guidelines were published in December 2023 [25].

This qualitative evidence synthesis was commissioned in parallel to several systematic reviews of evidence of benefits and harms of prioritized interventions for the Guideline, synthesized from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. These interventions were broad in scope, intensity and setting for delivery (reflected in the inclusion criteria for this synthesis). The aim of all the interventions is to improve health and wellbeing outcomes for people living with CPLBP. However, it is important to explore how this broad variation in interventions is perceived and experienced by older people with CPLBP and/or their caregivers (formal or informal, family members). Are some interventions more accepted than others? Are there differences between the interventions and/or access to them related to equity (gender, culture, place of residence, socio economic status) or setting (geographic or health care setting)? These important context questions can only be comprehensively answered using qualitative research methods. These contextual data are intended to support the development of the WHO guideline and complement additional perspectives brought to the development process by other stakeholders involved in the guideline development, consistent with WHO guideline development methods [45].

It is important to consider people’s preferences around interventions when formulating and implementing clinical management guidelines. In this paper we use the concept of person-centred care, in order to encompass a broader perspective than those related to being a patient. We have adopted the definition of person-centred care that is used in the WHO Guideline, that is “Person-centred care means eliciting an individual’s values, preferences and priorities: once expressed, they should guide all aspects of that person’s health care, supporting their personalized health and life goals” [46, 47].

An intervention may be proven effective but if it is not accepted by people living with the condition (and/or their carers) or they feel it causes burden or harm, it will not be adopted. An important step in a WHO guidelines development process is to consider what people living with CPLBP and their caregivers find acceptable? Feasible? Valued? [45] For example, there is a need to understand preferences and perspectives concerning accessibility, availability, affordability, perceived quality, burden [time, distance, frequency of visits], stigma, duration of therapeutic effect, person/patient’s role (passive or active role), immediacy of treatment effect, configuration of the care team– single practitioner or team approach, influence on comorbid health conditions, and symptoms related to the treatment. Some of these dimensions of value, preference and acceptability have been identified as previously as important to decision-making around treatments among older adults with osteoarthritis [48]. To date there has been some research conducted that considers people’s preferences for treatment for CPLBP [49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. However, to our knowledge, there has been no synthesis of primary qualitative research exploring the key factors influencing the implementation, uptake, and experience of interventions designed to manage CPLBP from the perspective of people aged over 60 and their caregivers.

The objective of this qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) was to understand the key factors influencing the acceptability of, and values and preferences/perspectives for, interventions/care for CPLBP from the perspective of people over 60 and their caregivers. The purpose of the QES was to inform the development of the WHO guideline [25].

Methods

This QES followed the best practice as described by the Cochrane collaboration in their handbook [56, 57]. The protocol was registered on PROSPERO at inception (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=328469).

We included primary studies with qualitative study designs. We included mixed-methods studies when it was possible to extract the data that were collected and analysed using qualitative methods. The inclusion criteria are described in Table 1.

We searched in two databases (MEDLINE and CINAHL powered by Ovid) (April 28, 2022) and supplemented the search with a search in an open-source dataset, OpenAlex [59, 60] (May 3, 2022) through the EPPI-Reviewer platform [59]. We also screened the references of the included studies. Finally, we asked members of the WHO Guideline Development Group to recommend any relevant research they were aware of.

To maximise efficiency of the study selection process, we used the machine learning function “priority screening” in the systematic review software EPPI-reviewer [61].

Two review authors (HA and CHH) independently assessed eligibility of the titles and abstracts. We retrieved the full text of all the papers identified as potentially relevant. Two authors (HA and CHH) then assessed the eligibility of these papers independently. Discrepancies in decisions were resolved by discussion among the authors.

Data extraction was performed using a data extraction form designed specifically for this review. One author performed the data extraction and a second author checked for accuracy against the source paper and any discordances were resolved through consensus discussion. We extracted the following information from the studies; author, year of publication, geographic setting, description of context, data collection methods (sampling, collection, and analysis), description of participants covering the aspects named in the inclusion table (see Table 1) and if ethics approval was given for the study.

We assessed the methodological limitations of the included studies using a list of domains iteratively developed by the Cochrane EPOC group [62,63,64,65]. We did not exclude studies based on our assessment of methodological limitations but used the information about methodological limitations to assess our confidence in the review findings.

We analysed the data by conducting a best fit framework synthesis [66,67,68,69]. Best fit framework synthesis is a qualitative synthesis method that blends deductive and inductive synthesis and analysis processes. As part of the synthesis method, review authors identify a conceptual framework that fits at least 50% of the data. After data extraction, data that does not fit within the framework is further analysed in order to develop a new framework that includes all of the data. We used the themes identified in the scoping review on older adults’ perceptions and experiences of integrated care by Lawless et al. [70], a conceptual framework from Chua et al. on choosing interventions for hip or knee osteoarthritis [48] as well as the PROGRESS Plus framework that addresses issues related to equity [71] to generate an a priori theoretical framework. We chose these frameworks as they were relevant to the topic we were exploring and expected to cover at least 50% of the data. The PROGRESS+ framework [71] was added to address the specific needs of the WHO guidelines process around equity, gender and human rights. HA moved the extracted data into the framework and CHH checked the data. We then analysed the data within each framework section and developed our findings. Relevant data that did not fit into the framework were analysed thematically. We used a thematic analysis approach as described by Miles and Huberman [72] as referred to in Carroll 2013 [66] in their paper on best fit framework synthesis. New themes were generated based on our interpretation of the evidence and constant comparison of the new themes across the included studies. In accordance with best fit framework synthesis methods, we inductively expanded the a priori framework to include a section on person-centred care and communication to reflect the breadth of all our findings.

Findings were then organized according to the domains defined in the WHO Handbook for Guideline Development that inform the determination of a recommendation, derived from qualitative evidence, including values and preferences, resource implications, equity and human rights, acceptability and feasibility (See Table 2).

Finally, we assessed our confidence in the findings using GRADE-CERQual [73]. We present detailed descriptions of our confidence assessment in Evidence Profile(s) [74].

In each section we present the summary of findings table and a summary of the main points discussed in the findings. For specific findings and our confidence in them please refer to Tables 4-9 (Summary of Qualitative Evidence Tables).

Review author reflexivity

Neither Heather Ames (HA), Christine Hillestad Hestevik (CHH) or Andrew Briggs (AMB) have reached the age of 60, so we do not understand the lived experience of being an older adult. HA is a previous elite athlete who has experience with chronic musculoskeletal pain and interventions due to injury and AMB has experience of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Both HA and AMB’s parents are over 60, have experienced chronic pain and have discussed their treatments with them. All authors support an evidence-based medicine approach to care. AMB is a clinician, researcher, and health systems professional in the field of chronic musculoskeletal pain. CHH does not have personal experience with chronic musculoskeletal pain or treatment interventions. She did her PhD on healthcare provided to older people from the perspectives of older persons, their family caregivers and healthcare professionals and has some experience with older persons experiences with encounters when in need of healthcare. These prior experiences, particularly a lived experience of chronic musculoskeletal pain, lead us to believe in the difficulties older people are facing. It also felt like the topics that were being raised were familiar from the perspective of personal and research experience.

Findings

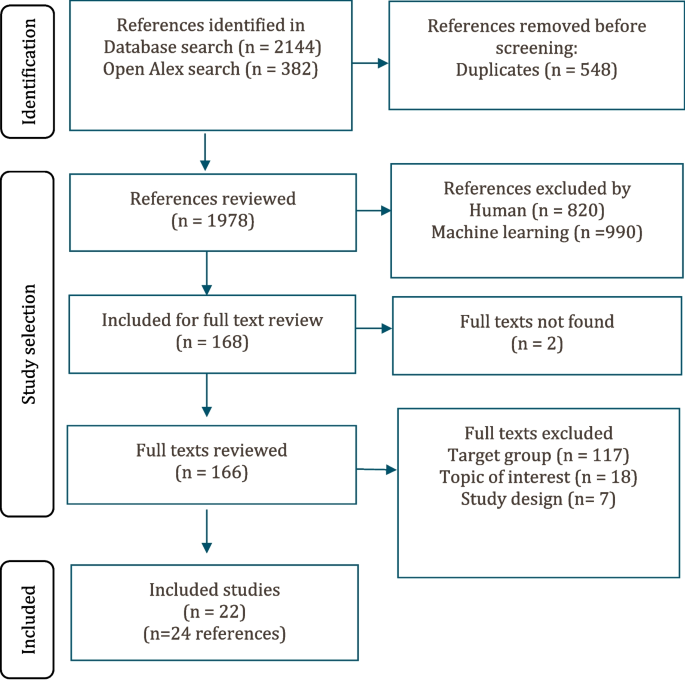

From a yield of 1878 unique citations, 22 studies were included in this review, reflected in 24 reports. See Fig. 1 for the study selection process. For a description of the included studies see Table 3.

The included studies were conducted in the United States (n = 8) [53, 54, 78, 90, 91, 93, 94, 96], United Kingdom (n = 3) [77, 79, 92], Germany (n = 2) [85, 86], Sweden (n = 2) [75, 87], Australia (n = 2) [84, 88, 89], Canada (n = 1) [80], Chile (n = 1) [95], Brazil (n = 1) [76], and Nigeria (n = 2) [81,82,83]. One study focused on Aboriginal Australians, a vulnerable population [88, 89]. In 14 of the studies all participants were aged 60 or older [53, 54, 77, 80, 84,85,86,87, 90, 91, 93,94,95,96]. In five, the mean or median age of the participants were 60 or older [75, 76, 78, 79, 92]. Three studies were included under the inclusion criteria for age for a low or middle-income country or identified vulnerable population [75, 81,82,83, 88, 89]. In these studies, the age of the participants ranged from 26 to 72 years, but we only used disaggregated results from participants aged 40 or above.

In 16 of the studies, the participants were community-dwelling older adults [53, 54, 76,77,78, 80,81,82,83, 87,88,89,90,91, 93,94,95,96]. Three of the studies were conducted in a primary health care setting but the residence of the participants was not discussed [75, 85, 86]. In three studies, the setting was unclear so we could not define the residence of the participants [79, 84, 92]. Nine of the studies were nested in a trial or a larger feasibility study [53, 54, 84, 86, 90,91,92,93,94].

We did not identify any studies that explored the perceptions or experiences of caregivers (formal or informal, family members).

Acceptability, values, and preferences

Since there was a large overlap in evidence related to values and preferences and acceptability, the findings are presented pooled. Values and preferences extended to interactions with health care providers, interventions for CPLBP and the modes of care delivery for CPLBP. Sixteen studies from 11 countries contributed to these findings (USA, Germany, Australia, United Kingdom, England, Scotland, Canada, Nigeria, Sweden, Brazil, and Chile). Participants in nine studies were all over 60 [54, 77, 80, 85, 87, 91, 93, 95, 96]. Four studies had participants with a mean or average age of 60 or older [75, 76, 79, 92] and four studies were from LMICs or vulnerable populations [76, 81,82,83, 88, 89] of which three were included based on a lowered age threshold [81,82,83, 88, 89]. In 13 of the studies most of the participants were women (53–83%) [54, 75,76,77, 79,80,81,82, 85, 87, 91, 93, 95, 96]. In two studies [83, 92] there was an equal distribution of men and women. In one study most participants were men (52–66% men) [88, 89].

Interactions with health care providers

Most participants wanted their health care providers to collaborate and work together to provide holistic care for their CPLBP. There was a preference among participants for providers who were respectful, caring, person-centred, collaborative, open to discussing treatment options and provided individualized care. They preferred health care providers who recognized them and their pain as individual and unique. This type of care allowed them to feel safe and feel they had meaningful relationships. When this was lacking, they could feel frustrated, vulnerable and experience a sense of aloneness (high confidence) [75, 79, 83, 88, 89, 91, 93, 95, 96].

Participants generally emphasized the care should be person-centred and provide continuity. They also identified a preference for a collaborative communication style which meant involving the older person in discussions about diagnosis and treatment options and viewing them as the expert on their own body (low confidence) [77, 79, 80, 88, 91].

Participants wanted collaboration and communication across their care teams to ensure co-ordinated care delivery and avoid duplication in care or diagnostics (moderate confidence) [75, 88, 91]. Some participants felt that they often received conflicting advice or information from health care providers. Participants valued receiving a diagnosis as this influenced their treatment decisions. The way the diagnosis was communicated could also shape their beliefs and responses to pain (moderate confidence) [76, 79, 81, 83, 85, 89, 91, 92, 95]. Some participants expressed dissatisfaction with health care providers for being unwilling to discuss treatment options other than medication (low confidence) [75, 93, 96]. The summary of findings is presented in Table 4.

Values and preferences for CPLBP interventions in older people

Participants had clear values and preferences for how they chose a specific treatment for CPLBP. A choice of treatment could be influenced by previous experiences. Participants valued treatments that they viewed as effective, beneficial, and credible and fit them as individuals (high confidence) [53, 54, 79,80,81,82, 84,85,86,87, 93, 95, 96].

Most participants used and valued medication for its ability to provide short-term pain relief. However, many participants did not like the side effects associated with medications or the way the medication(s) made them feel (moderate confidence) [53, 78, 79, 91, 93, 96]. Many also feared addiction, especially in relation to opioid analgesics. In some cases, participants adjusted or stopped medication without consulting their health care provider because of fears of adverse events (moderate confidence) [53, 79, 91, 96, 97].

Mindfulness and meditation encouraged participants to examine, assess, understand, and accept their pain rather than avoid it. Participants were able to use mindfulness and meditation for pain management and coping to varying degrees (moderate confidence) [54, 90, 94]. The summary of the findings is presented in Table 5.

Format of interventions and educational materials for CPLBP in older people

Participants discussed their experiences with, and views of, organized and unorganized physical therapies and activities. Specific physical interventions were rarely mentioned. For many participants, physical activity was an important aspect of coping with their CPLBP. Many participants preferred a group format for physical exercises as it facilitated social support, collaboration and encouraged increased attendance (moderate confidence) [54, 79,80,81,82, 85]. Some participants also expressed preferences for educational material for physical interventions which had drawings and descriptions of the exercises. This made them more comprehensible, easier to follow and helpful for present and future reference (low confidence) [79, 81, 82, 85, 86].

Peer support interventions appeared to be acceptable and valued by some older people. They were seen as an acceptable way of gaining support and sharing information or advice. Participants mostly viewed peer support as feasible as it could be delivered through several different modalities (for example, face to face, in groups or online) that would fit individual preferences and lifestyles. However, it was clear that peer support was difficult to find and access in some settings, although appeared to be valued as a component of overall self-management of a CPLBP experience (low confidence) [77, 78, 80, 92, 96] [77, 78, 80, 92, 96].. The summary of the findings is presented in Table 6.

Cost/resources related to CPLBP care in older people

Seven studies from five countries contributed to these findings (USA, Australia, England, Nigeria, and Sweden). Participants in three studies were all over 60 [53, 84, 91], two studies had participants with a mean or average age of 60 or older [75, 79] and two studies were from LMICs or vulnerable populations of which both were included based on a lowered age threshold [83, 88, 89]. In five of the studies most of the participants where women (55–100%) [53, 75, 79, 84, 91]. In one study there was an equal distribution between men and women [83]. In one study most participants were men (66%) [88, 89].

We found that cost and resources could be a barrier to accessing care for CPLBP for some participants. High costs (financial, time and travel) could render treatments inaccessible to participants or acts as a deterrent (moderate confidence) [53, 79, 83, 91]. Many also preferred health care providers near where they lived to minimise travel burden. However, some participants were willing to travel if a trusted or favoured provider relocated, or they wanted to explore new treatment options. Others chose to find a new practitioner closer to them in this situation (moderate confidence) [53, 75, 79, 83, 84, 88, 91]. The summary of the findings is presented in Table 7.

Feasibility

Twelve studies from eight countries contributed to these findings (USA, Canada, UK, Australia, England, Scotland, Nigeria, Chile). Participants in seven studies were all over 60 [53, 77, 80, 84, 91, 95, 96]. Three studies had participants with a mean or average age of 60 or older [78, 79, 92] and two studies were from LMICs or vulnerable populations of which both were included based on a lowered age threshold [81,82,83]. In 10 of the studies most of the participants where women (62–100%) [53, 77,78,79,80,81,82, 84, 91, 95, 96]. In two studies there was about an equal distribution between men and women [83, 92].

Some participants found information about treatments difficult to access and wanted help finding it or navigating the information from a health or care worker or through a peer support system. They felt that this could help them make decisions (low confidence) [78, 79, 84, 92, 96].

Physical activity and/or exercise was used a part of a self-management strategy for many participants. Activities such as swimming and walking were often mentioned as being done in their own time and when it fit their schedule. Some participants adopted physical exercise, assistive products, or alternative forms of treatment to supplement the conventional treatments they were receiving or when they felt “conventional treatments” failed. However, some did not inform their health care providers about their self-management strategies or changes they had made (moderate confidence). The summary of findings is presented in Table 8.

Equity and human rights

Seven studies from six countries contributed to this finding (USA, Canada, UK, England, Scotland, and Sweden, Brazil). Participants in four studies were all over 60 [77, 80, 91, 93] and three studies had participants with a mean or average age of 60 or older [75, 79, 92]. In six of the studies most of the participants were women [75, 77, 79, 80, 91, 93]. In one study there was an equal distribution of men and women [92].

Some participants perceived age-related stigma or bias when accessing healthcare for their CPLBP. They reported feeling that they were treated differently, dismissed, or discriminated against because of their age. They felt they were not taken seriously. This perceived stigma could deter them from seeking further treatment. However, in other cases participants believed that they were taken more seriously as they aged (Low confidence). The summary of the finding is presented in Table 9.

Additions to the framework

To incorporate all the data we analysed we expanded the framework to include a section we labelled person centred care.

Discussion

Main findings

Based on this synthesis of qualitative evidence derived from more than 650 older participants across 22 studies with representation across a range of geographies and economic contexts, we identified that older people living with CPLBP express values and preferences for their care that relate to therapeutic encounters and the importance of therapeutic alliance, irrespective of the type of treatment offered or delivered, choice of intervention, and intervention delivery modalities. Older people with CPLBP value therapeutic encounters that validate, legitimise, and respect their pain experience; that consider their context holistically and prioritise their needs and preferences; that adopt a person-focused and tailored approach to care; and that are supported by interprofessional communication. Older people value care that provides benefit to them, that includes a suite of interventions beyond analgesic medicines alone, and that is financially and geographically accessible. These findings provide critical context to service delivery models for older people; formulation of recommendations for guidelines that relate to older people; and service considerations for the implementation of clinical guidelines into practice, particularly related to how health care workers interact with older people, with attention to potential age-related bias, and how components of care are delivered.

Person-centred care for older adults living with CPLBP

Many older people felt that healthcare providers did not legitimise their pain and that pain was deprioritised relative to other health conditions. Musculoskeletal pain, including CPLBP, is a common experience in older people [98, 99] and a very frequent co-morbidity with other noncommunicable diseases [100]. Therefore, pain assessment is a key component of the WHO Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) assessment and care pathway [101]. Comorbidities more strongly associated with mortality or acute health declines can make it difficult for health professionals to prioritise symptoms of CPLBP in time-limited clinical encounters. There seems to be a difference between patient and care provider priorities when it comes to pain management and our findings point to the need to legitimise and respond to pain as this clearly is a priority for older people, consistent with recently reported evidence [55]. Our findings point to the importance of the therapeutic relationship and communication between older people and care providers to understand the impact of, and preference for, CPLBP care. Older people also experienced issues linked to equity during the therapeutic encounter. These could be expressed through ageism and stigma associated with CPLBP. Being told to ‘just live with it’, or the idea that CPLBP was an inevitable part of ageing were common and suggest a potential age-related bias among healthcare providers. Being aware of potential clinician bias related to chronic pain in older people is important, since ageism is associated with poorer health outcomes, particularly in low resource settings [102].

The needs and priorities of older people may well differ to younger adults (e.g. return to work, taking care of dependents, intensity of everyday activities or sport may be less important for older people). There are previous findings of the perceived needs of adult groups with CPLBP [103, 104]. Consistent with other reviews among adults, we identified that older people value clear and consistent information, a clear diagnosis, prognosis, and a communication style that is meaningful and avoids jargon [105]. Communication that emphasises disability or impairments can be unhelpful to fostering pain self-efficacy, contribute to fear, unhelpful care seeking and further compound disability [106,107,108,109], which will foster healthy ageing. Rather, providing empowering and positive communication that is validating, helping to make sense of pain and the likelihood of a positive prognosis, providing cognitive reassurance and clear information about benefits and harms of interventions (in particular, medicines) can support shared decision-making, positive behaviour change towards effective self-management, and better engagement in meaningful activities [110]; all important for supporting healthy ageing.

We identified a preference for integrated and coordinated CPLBP care across care providers and facilities, consistent with the WHO ICOPE model [101]. This includes holistic care planning with comprehensive assessments and care plans aligned with the person’s values, priorities and preferences concerning their care. The older person should be involved with decision-making and goal-setting from the the start of their care journey. The care should be regular and include sustained follow-up, with integration and communication across different levels of care. This approach to care can help to avoid unnecessary treatments, polypharmacy and other potential harms [47, 110]. Our findings about fears of side effects, dependency and medicine withdrawal or non-adherence also points to the need for clinicians to take time to explain risk-benefits of different medicines so that older people understand what medicines are for and how to use them safely.

Values and preferences were largely agnostic to intervention modality, other than values relating to medicines, where specific issues related to fear of adverse events were observed. Although analgesic medicines were considered important for CPLBP care, older people preferred care packages that extend beyond analgesia so that care is more holistic and considers safety (e.g. issues of dependency for opioid analgesics) and that were meaningful and personally enjoyable – such as social benefits of group exercise. Recent evidence points to the importance of considering pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies for CPLBP care, consistent with the experiences, values and preferences of older people [97]. Other evidence highlights care needs also extend beyond biomedical domains [24, 103]. Specifcally, tailoring components of care that addresses pain, emotional and social wellbeing, consistent with WHO ICOPE [101] model for improving functional ability, is important.

Implementing and delivering care for older people living with CPLBP

When developing, implementing, and delivering interventions for older people who experience functional disability related to musculoskeletal pain (or other co-morbidities), consideration of economic, social, and cultural contexts is critical. Many experienced financial and geographic barriers to care. Access to care that is expensive (or not included in UHC or insurance rebates), that requires travel, or accessing buildings that are not adapted for people experiencing functional disability can be problematic. This threat is more severe for those living in poverty without access to healthcare or who cannot afford to access healthcare near them, such as in low-resource settings. This lack of access may lead to worse outcomes for older people living in these settings, widening inequities in access to health care and health outcomes. Services also need to consider the user’s social context [111]. If not taken into account, pain care is likely to be inequitable and inaccessible. Support needs to go beyond the purely biomedical (especially focusing on medication) and encompass interventions that address peer support and socialization as well as issues around acceptability and stigma. Interventions should be tailored to local contexts to increase social and cultural approval. Some of the interventions included in this synthesis, such as exercise, were stigmatized in some settings [81,82,83]. Other research has also found that stigma can be associated with gender [112] or with interventions targeted at older people [113].

Older people also wanted support for the implementation of interventions such as guidance on how to perform exercises in the form of drawings and text. None of the studies we included talked about digital supports except for those related to peer support where digital meetings were discussed. While some formative evidence exists around the role of digital technologies to support healthy ageing [114,115,116], further research is required to understand users’ perspectives, benefits and harms in different contexts and among different population groups. Other research has also shown the acceptability of peer support in older adults with CPLBP [117]. Research on older people has found that they access digital tools but may face barriers such as physical mobility, sight and hearing impairment and low digital literacy when trying to use them [118,119,120]. Studies examining the use of digital tools for interventions for low back pain not limited to older people have found that users value models that are easily understandable, provide an opening to further communication with health care providers, family and colleagues and can provide prompts, reassurance, ongoing support and interaction with other users [121, 122].

These empirical findings hold direct relevance to the formulation of recommendations in guidelines and implementation of recommended care within service models and local care pathways. In this context, the current QES has informed the development of the WHO Guideline for non-surgical management of chronic primary low back pain in adults in primary and community care settings [25]. Without consideration of the fundamental EtD factors (Table 2) and the evidence underpinning each when formulating recommendations for guidelines or implementation plans for service models, as presented in our QES, care recipients (and in some cases, care providers) may not accept or be able to access care, manifesting as an enduring disease burden and inequity in health outcomes. The QES findings, when coupled with evidence for benefit, harm, cost effectiveness and implementation feasibility and lived experience perspectives that contribute to co-creation of solutions (care recommendations, service models, care pathways) that are more likely to be implemented, sustainable and acceptable [123]. Indeed, consideration of qualitative evidence anchored to EtD domains is common practice for WHO guidelines [45].

Implications for research

There was a clear lack of research from low- and middle-income settings as well as vulnerable populations in all settings. Most of the included studies explored the perceptions of community dwelling older adults. More research on the experiences of older adults living in residential care or other settings could help to broaden our understanding. Very few of the studies explored perceptions of specific interventions. Most looked at treatment across interventions and participants did not differentiate between interventions in the same way a health care provider would. For example, participants viewed the visit to the physiotherapist as the intervention whereas health care providers would view each of the treatments received as individual interventions. One topic not frequently discussed in the included studies was cost and out of pocket expenses. This may be because several studies were conducted as part of a trial where participants did not pay to access the intervention. Cost was also rarely discussed in studies taking place in publicly funded health care systems. Understanding affordability of care, willingness to pay and inequities in access to care due to cost will be important in planning implementation of health services for CPLBP care for older people. Further research is also needed on the perspectives and experiences of caregivers as there were no studies identified that explored this topic of interest.

Implications for practice

The questions that form our implications for practice are derived from our findings with moderate or high confidence. They may help health system or program managers to plan, implement or manage interventions for CPLBP. It is important to consider local contextual factors including gender, age, cultural group, and education when implementing interventions.

-

Is the burden to access services low (financial, time and travel)? Have issues related to burden and equity of access been considered?

-

When planning, implementing, or managing an intervention for CPLBP or communicating with people over 60 with CPLBP:

-

◦ have participants values and preferences been explored and taken into consideration?

-

◦ are participants informed about the physical exercise or physical supports available to them?

-

-

When communicating with adults over 60 with CPLBP, have values and preferences been considered, regarding:

-

◦ communication, cultural preferences, and health care provider collaboration?

-

◦ receiving a diagnosis and preferences for information?

-

-

When prescribing medication, do health care workers provide open and honest communication with their patients about medications, the risk of side effects, and the risk of dependency, inviting them to return with concerns and informing of the importance of working together to manage their medications?

Conclusion

Older people with CPLBP value therapeutic encounters that legitimise and respect their pain experience, that consider their context holistically and prioritises their needs and preferences, that is tailored, and that is supported by interprofessional communication. Older people value care that provides benefit, that includes interventions beyond analgesic medicines alone, and that is financially and geographically accessible. These findings provide critical context to the implementation of clinical guidelines and service models into practice, particularly related to how care providers interact with older people and how components of care are delivered and their accessibility.

Availability of data and materials

All the studies in this synthesis are published and available. The data that is in each finding is available in an interactive Summary of Qualitative Findings table. For access to this tool please send an email to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- CPLBP:

-

Chronic primary low back pain

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- QES:

-

Qualitative evidence synthesis

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- UHC:

-

Universal health coverage

- ICOPE:

-

Integrated care for older people

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, Hanson SW, Chatterji S, Vos T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the global burden of disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10267):2006–17.

Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–22.

Ferreira ML, de Luca K, Haile LM, Steinmetz JD, Culbreth GT, Cross M, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(6):e316-ee29.

Gill TK, Mittinty MM, March LM, Steinmetz JD, Culbreth GT, Cross M, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of other musculoskeletal disorders, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(11):e670-ee82.

Black RJ, Cross M, Haile LM, Culbreth GT, Steinmetz JD, Hagins H, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(10):e594–610.

Beyera GK, O’Brien J, Campbell S. Health-care utilisation for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based observational studies. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(10):1663–79.

Vigdal ØN, Storheim K, Killingmo RM, Småstuen MC, Grotle M. Characteristics of older adults with back pain associated with choice of first primary care provider: a cross-sectional analysis from the BACE-N cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e053229.

Wong AY, Karppinen J, Samartzis D. Low back pain in older adults: risk factors, management options and future directions. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2017;12(1):1–23.

Paeck T, Ferreira ML, Sun C, Lin CWC, Tiedemann A, Maher CG. Are older adults missing from low back pain clinical trials? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66(8):1220–6.

Carvalho do Nascimento PR, Ferreira ML, Poitras S, Bilodeau M. Exclusion of older adults from ongoing clinical trials on low back pain: a review of the WHO trial registry database. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(3):603–8.

Rittweger J, Just K, Kautzsch K, Reeg P, Felsenberg D. Treatment of chronic lower back pain with lumbar extension and whole-body vibration exercise: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2002;27(17):1829–34.

Hutchinson AJ, Ball S, Andrews JC, Jones GG. The effectiveness of acupuncture in treating chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. J Orthop Surg Res. 2012;7(1):1–8.

Yerlikaya M, Saracoglu İ. The attitudes and beliefs of physiotherapists, family physicians and physiatrists concerning chronic low back pain. J Health Sci Med. 5(2):393–8.

La Touche R, Escalante K, Linares MT. Treating non-specific chronic low back pain through the Pilates method. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2008;12(4):364–70.

Senderovich H, Wagman H, Zhang D, Vinoraj D, Waicus S. The effectiveness of Cannabis and Cannabis derivatives in treating lower Back pain in the aged population: a systematic review. Gerontology. 2021;68:1–13.

Netchanok S, Wendy M, Marie C. The effectiveness of Swedish massage and traditional Thai massage in treating chronic low back pain: a review of the literature. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2012;18(4):227–34.

Wu L-C, Weng P-W, Chen C-H, Huang Y-Y, Tsuang Y-H, Chiang C-J. Literature review and meta-analysis of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in treating chronic back pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(4):425–33.

Owen PJ, Miller CT, Mundell NL, Verswijveren SJ, Tagliaferri SD, Brisby H, et al. Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain? Network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(21):1279–87.

Kolber MR, Ton J, Thomas B, Kirkwood J, Moe S, Dugré N, et al. PEER systematic review of randomized controlled trials: management of chronic low back pain in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2021;67(1):e20–30.

Pillastrini P, Gardenghi I, Bonetti F, Capra F, Guccione A, Mugnai R, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for chronic low back pain management in primary care. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(2):176–85.

World Health Organization. Development of WHO Guideline on management of chronic primary low back pain in adults. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-health-and-ageing/ageing-and-health/integrated-care-for-older-people-icope/development-of-who-guideline-on-management-of-chronic-primary-low-back-pain-in-adults. Accessed 1 Sept 2023.

Cesari M, Sumi Y, Han ZA, Perracini M, Jang H, Briggs A, et al. Implementing care for healthy ageing. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(2):e007778.

Lee D-CA, Burton E, Slatyer S, Jacinto A, Oliveira D, Bryant C, et al. Understanding the role, quality of life and strategies used by older carers of older people to maintain their own health and well-being: a national Australian survey. Clin Interv Aging. 2022;17:1549–67.

Slater H, Jordan JE, O’Sullivan PB, Schütze R, Goucke R, Chua J, et al. ‘Listen to me, learn from me’: a priority setting partnership for shaping interdisciplinary pain training to strengthen chronic pain care. Pain. 2022;163.

WHO guideline for non-surgical management of chronic primary low back pain in adults in primary and community care settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081789. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Cancelliere C, Hincapié C, Bussières A, Gross D, Pereira P, Mior S, et al. Education or advice for chronic primary low back pain in adults; A systematic review protocol. PROSPERO; 2022.

Cancelliere C, Hayden J, Ogilvie R, Hincapié C, Bussières A, Gross D, et al. Exercise therapy for chronic primary low back pain in adults; A systematic review protocol. PROSPERO; 2022.

Rubinstein S, de Zoete A, Innocenti T, Maas E, Pellekooren S, Chiarotto A, et al. Systematic review on the effect of spinal manipulative therapy in people with chronic primary low back pain (protocol). PROSPERO; 2022.

Maas E, Pellekooren S, Ostelo R, Innocenti T, Chiarotto A, de Zoete A, et al. Systematic review on the effect of massage therapy in people with chronic primary low back pain (protocol). PROSPERO; 2022.

Pellekooren S, Maas E, Wegner I, Ostelo R, Innocenti T, Chiarotto A, et al. Systematic review on the effect of traction in people with chronic primary low back pain (protocol). PROSPERO; 2022.

Cancelliere C, Hincapié C, Bussières A, Gross D, Pereira P, Mior S, et al. Acupuncture for chronic primary low back pain in adults (protocol). PROSPERO; 2022.

Cancelliere C, Hincapié C, Bussières A, Gross D, Pereira P, Mior S, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic primary low back pain in adults (protocol). PROSPERO; 2022.

Probyn K, Petkovic J, Cogo E, Bergman H, Arienti C, Negrini S, et al. Protocolfor a systematic review on therapeutic ultrasound for chronic primary low back painin adults. Open science framework; 2022.

Probyn K, Villannueva G, Cogo E, Bergman H, Petkovic J, Conde M, et al. Protocolfor a systematic review on psychosocial therapies for chronic primary low back painin adults. Open science framework; 2022.

Chou R, Dana T. Pharmacotherapies for chronic primary low back pain: systematic review to inform the WHO global guideline on chronic primary low back pain in adults (protocol). PROSPERO; 2022.

Wewege M, Bagg M, Jones M, McAuley J. Analgesic medicines for adults with low back pain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis (protocol). PROSPERO.; 2019.

Chou R, Hartung D, Turner J, Blazina I, Chan B, Levander X, et al. Opioid treatments for chronic pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 229. (Prepared by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2015-00009-I.) 2020.

McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, Holmes RS, Mauer K, Ramirez S, et al. Nonopioid pharmacologic treatments for chronic pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228.; 2020.

Chou R, Pinto RZ, Fu R, Lowe RA, Henschke N, McAuley JH, et al. Systemic corticosteroids for radicular and non-radicular low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;10.

Probyn K, Villannueva G, Cogo E, Bergman H, Conde M, Negrini S, et al. Protocolfor a systematic review on localanaesthetic agents for chronic primary lowback painin adults. Open science framework; 2022.

McDonagh M, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, Fu R, Morasco B, Kansagara D, et al. Living systematic review on Cannabis and other plant-based treatments for chronic pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 250. . 2021.

Probyn K, Villannueva G, Chi Y, Cogo E, Conde M, Berman B, et al. Protocolfor a systematic review on herbal medicinesfor chronic primary low back painin adults. Open science framework; 2022.

Williams C, Tutty A, Cashin A, McAuley J, Kamper S, Michaleff Z, et al. Effectiveness of weight management intervention for chronic primary low back pain care: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis to inform the WHO global guideline on low back pain in adults. PROSPERO; 2022.

Probyn K, Villannueva G, Bergman H, Arienti C, Minozzi S, Lazzarini SG, et al. Protocolfor a systematic review on biopsychosocial rehabilitationfor chronic primary low back painin adults. Open science framework; 2022.

World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development. World Health Organization; 2014.

Care AGSEPoPC, Brummel-Smith K, Butler D, Frieder M, Gibbs N, Henry M, et al. Person-centered care: a definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):15–8.

Hutting N, Caneiro J, Ong'wen OM, Miciak M, Roberts L. Person-centered care for musculoskeletal pain: Putting principles into practice. Musculoskelet Sci Pract.. 2022:102663.

Chua J, Briggs AM, Hansen P, Chapple C, Abbott JH. Choosing interventions for hip or knee osteoarthritis-what matters to stakeholders? A mixed-methods study. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2020;2(3):100062.

Kløjgaard ME, Manniche C, Pedersen LB, Bech M, Søgaard R. Patient preferences for treatment of low back pain—a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2014;17(4):390–6.

Staats P, Deer T, Ottestad E, Erdek M, Spinner D, Gulati A. Understanding the role of patient preference in the treatment algorithm for chronic low back pain: results from a survey-based study. Pain Manag. 2021;12.

Walsh DA, Boeri M, Abraham L, Atkinson J, Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC, et al. Exploring patient preference heterogeneity for pharmacological treatments for chronic pain: a latent class analysis. Eur J Pain. 2022;26(3):648–67.

Rutgers KM. Shared decision making in physical therapy treatments of people with intermittent claudication, before and after the implementation of KomPas; a pre-post study. 2021. Master's Thesis.

Stensland M. Managing the incurable: older pain clinic Patients’ experiences of managing treatment-resistant chronic low Back pain. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2021;64(4):405–22.

Lee TLSK, Hawkes RJ, Phelan EA, Turner JA. The benefits of T'ai Chi for older adults with chronic Back pain: a qualitative study. J Altern Complement Med. 2020;26(6):456–62.

Slater H, Jordan JE, O'Sullivan PB, Schütze R, Goucke R, Chua J, et al. “Listen to me, learn from me”: a priority setting partnership for shaping interdisciplinary pain training to strengthen chronic pain care. Pain. 2022;10(1097).

Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, Flemming K, Harden A, Harris J, et al. Qualitative evidence. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions; 2019. p. 525–45.

Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JW, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Benoliel R, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain. 2019;160(1):28–37.

OpenAlex. OpenAlex documentation 2022 [Available from: https://docs.openalex.org/.

Priem J, Piwowar H, Orr R. OpenAlex: A fully-open index of scholarly works, authors, venues, institutions, and concepts. arXiv preprint arXiv:220501833. 2022.

Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-reviewer 4: software for research synthesis. EPPI-Centre software. London: Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education; 2010.

Ames HM, Glenton C, Lewin S. Parents' and informal caregivers' views and experiences of communication about routine childhood vaccination: a synthesis of qualitative evidence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2.

Ames HM, Glenton C, Lewin S, Tamrat T, Akama E, Leon N. Clients’ perceptions and experiences of targeted digital communication accessible via mobile devices for reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10.

Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Lewin S, Fretheim A, Nabudere H. Factors that influence the provision of intrapartum and postnatal care by skilled birth attendants in low-and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11.

Glenton C, Carlsen B, Lewin S, Wennekes MD, Winje BA, Eilers R. Healthcare workers’ perceptions and experiences of communicating with people over 50 years of age about vaccination: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;7.

Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, Rick J. “Best fit” framework synthesis: refining the method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):1–16.

Booth A, Carroll C. How to build up the actionable knowledge base: the role of ‘best fit’framework synthesis for studies of improvement in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(11):700–8.

Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K. A worked example of" best fit" framework synthesis: a systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):1–9.

Brunton G, Oliver S, Thomas J. Innovations in framework synthesis as a systematic review method. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11(3):316–30.

Lawless MT, Marshall A, Mittinty MM, Harvey G. What does integrated care mean from an older person’s perspective? A scoping review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e035157.

O’Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V, Petticrew M, Pottie K, Clarke M, et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(1):56–64.

Huberman M, Miles MB. The qualitative researcher’s companion. Sage; 2002.

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. BioMed Central; 2018.

Lewin S, Bohren M, Rashidian A, Munthe-Kaas H, Glenton C, Colvin CJ, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 2: how to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a summary of qualitative findings table. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):11–23.

Allvin R, Fjordkvist E, Blomberg K. Struggling to be seen and understood as a person - chronic back pain patients’ experiences of encounters in health care: an interview study. Nurs Open. 2019;6(3):1047–54.

Bonfim IDS, Correa LA, Nogueira LAC, Meziat-Filho N, Reis FJJ, de Almeida RS. Your spine is so worn out - the influence of clinical diagnosis on beliefs in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain - a qualitative study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2021;25(6):811–8.

Cooper K, Schofield P, Klein S, Smith BH, Jehu LM. Exploring peer-mentoring for community dwelling older adults with chronic low back pain: a qualitative study. Physiotherapy. 2017;103(2):138–45.

Cummings EC, van Schalkwyk GI, Grunschel BD, Snyder MK, Davidson L. Self-efficacy and paradoxical dependence in chronic back pain: a qualitative analysis. Chronic Illness. 2017;13(4):251–61.

Dima A, Lewith GT, Little P, Moss-Morris R, Foster NE, Bishop FL. Identifying patients’ beliefs about treatments for chronic low back pain in primary care: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(612):e490–8.

Hay ME, Connelly DM. Exploring the experience of exercise in older adults with chronic Back pain. J Aging Phys Act. 2020;28(2):294–305.

Igwesi-Chidobe CN, Godfrey EL, Kitchen S, Onwasigwe CN, Sorinola IO. Community-based self-management of chronic low back pain in a rural African primary care setting: a feasibility study. Primary Health Care Res Dev. 2019;20:e45.

Igwesi-Chidobe CN, Kitchen S, Sorinola IO, Godfrey EL. Evidence, theory and context: using intervention mapping in the development of a community-based self-management program for chronic low back pain in a rural African primary care setting - the good back program. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):343.

Igwesi-Chidobe CN, Kitchen S, Sorinola IO, Godfrey EL. “a life of living death”: the experiences of people living with chronic low back pain in rural Nigeria. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(8):779–90.

Kirby ER, Broom AF, Adams J, Sibbritt DW, Refshauge KM. A qualitative study of influences on older women’s practitioner choices for back pain care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:131.

Kuss K, Leonhardt C, Quint S, Seeger D, Pfingsten M, Wolf P, et al. Graded activity for older adults with chronic low Back pain: program development and mixed methods feasibility cohort study. Pain Med. 2016;17(12):2218–29.

Leonhardt C, Kuss K, Becker A, Basler H-D, de Jong J, Flatau B, et al. Graded exposure for chronic low Back pain in older adults: a pilot study. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2017;40(1):51–9.

Lilje SC, Olander E, Berglund J, Skillgate E, Anderberg P. Experiences of older adults with Mobile phone text messaging as reminders of home exercises after specialized manual therapy for recurrent low Back pain: a qualitative study. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2017;5(3):e39.

Lin I, O’Sullivan P, Coffin J, Mak DB, Toussaint S, Straker L. “I can sit and talk to her”: Aboriginal people, chronic low back pain and healthcare practitioner communication. Aust Fam Physician. 2014;43(5):320–4.

Lin IB, O'Sullivan PB, Coffin JA, Mak DB, Toussaint S, Straker LM. Disabling chronic low back pain as an iatrogenic disorder: a qualitative study in Aboriginal Australians. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4).

Luiggi-Hernandez JG, Woo J, Hamm M, Greco CM, Weiner DK, Morone NE. Mindfulness for chronic low Back pain: a qualitative analysis. Pain Med. 2018;19(11):2138–45.

Lyons Kevin J, Salsbury Stacie A, Hondras Maria A, Hondras Maria A, Jones Mark E, Andresen Andrew A, et al. Perspectives of older adults on co-management of low back pain by doctors of chiropractic and family medicine physicians: a focus group study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13(1):225.

MacKichan F, Paterson C, Britten N. GP support for self-care: the views of people experiencing long-term back pain. Fam Pract. 2013;30(2):212–8.

Makris Una E, Makris Una E, Higashi Robin T, Marks Emily G, Fraenkel L, Fraenkel L, et al. Ageism, negative attitudes, and competing co-morbidities – why older adults may not seek care for restricting back pain: a qualitative study. Bmc Geriatrics. 2015;15(1):39.

Morone NE, Lynch CS, Greco CM, Tindle HA, Weiner DK. “I felt like a new person” the effects of mindfulness meditation on older adults with chronic pain: qualitative narrative analysis of diary entries. J Pain. 2008;9(9):841–8.

Rodriguez I, Abarca E, Herskovic V, Campos M. Living with chronic pain: a qualitative study of the daily life of older people with chronic pain in Chile. Pain Res Manag. 2019;2019:8148652.

Teh Carrie F, Karp Jordan F, Kleinman Arthur M, Reynolds Charles F, Weiner Debra L, Cleary PD. Older People’s experiences of patient-centered treatment for chronic pain: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2009;10(3):521–30.

Makris UE, Higashi RT, Marks EG, Fraenkel L, Gill TM, Friedly JL, et al. Physical, emotional, and social impacts of restricting back pain in older adults: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2016;18(7):1225–35.

Wong CK, Mak RY, Kwok TS, Tsang JS, Leung MY, Funabashi M, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with non-specific chronic low back pain in community-dwelling older adults aged 60 years and older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2022;23(4):509–34.

De Souza IMB, Sakaguchi TF, Yuan SLK, Matsutani LA, do Espírito-Santo AdS, Pereira CAdB, et al. Prevalence of low back pain in the elderly population: a systematic review. Clinics. 2019;74.

Simões D, Araújo FA, Severo M, Monjardino T, Cruz I, Carmona L, et al. Patterns and consequences of multimorbidity in the general population: there is no chronic disease management without rheumatic disease management. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(1):12–20.

World Health Organization. Integrated care for older people (ICOPE): guidance for person-centred assessment and pathways in primary care. World Health Organization; 2019.

Chang ES, Kannoth S, Levy S, Wang SY, Lee JE, Levy BR. Global reach of ageism on older persons’ health: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0220857.

Chou L, Cicuttini FM, Urquhart DM, Anthony SN, Sullivan K, Seneviwickrama M, et al. People with low back pain perceive needs for non-biomedical services in workplace, financial, social and household domains: a systematic review. J Phys. 2018;64(2):74–83.

Van Rysewyk S, Blomkvist R, Chuter A, Crighton R, Hodson F, Roomes D, et al. Understanding the lived experience of chronic pain: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative evidence syntheses. Br J Pain. 2023;17:20494637231196424.

Lim YZ, Chou L, Au RT, Seneviwickrama KMD, Cicuttini FM, Briggs AM, et al. People with low back pain want clear, consistent and personalised information on prognosis, treatment options and self-management strategies: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2019;65(3):124–35.

O’Keeffe M, Ferreira GE, Harris IA, Darlow B, Buchbinder R, Traeger AC, et al. Effect of diagnostic labelling on management intentions for non-specific low back pain: a randomized scenario-based experiment. Eur J Pain. 2022;26(7):1532–45.

O’Keeffe M, Michaleff ZA, Harris IA, Buchbinder R, Ferreira GE, Zadro JR, et al. Public and patient perceptions of diagnostic labels for non-specific low back pain: a content analysis. Eur Spine J. 2022;31(12):3627–39.

Sloan TJ, Walsh DA. Explanatory and diagnostic labels and perceived prognosis in chronic low Back pain. Spine. 2010;35(21).

Darlow B, Fullen BM, Dean S, Hurley DA, Baxter GD, Dowell A. The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2012;16(1):3–17.

Belton J, Birkinshaw H, Pincus T. Patient-centered consultations for persons with musculoskeletal conditions. Chiropr Man Ther. 2022;30(1):53.

Ashton-James CE, Anderson SR, Mackey SC, Darnall BD. Beyond pain, distress, and disability: the importance of social outcomes in pain management research and practice. Pain. 2022;163(3):e426-ee31.

Ruissen GR, Liu Y, Schmader T, Lubans DR, Harden SM, Wolf SA, et al. Effects of group-based exercise on flourishing and stigma consciousness among older adults: findings from a randomised controlled trial. Appl Psychol: Health Well-Being. 2020;12(2):559–83.

Bunn F, Dickinson A, Barnett-Page E, Mcinnes E, Horton K. A systematic review of older people’s perceptions of facilitators and barriers to participation in falls-prevention interventions. Ageing Soc. 2008;28(4):449–72.

Ienca M, Schneble C, Kressig RW, Wangmo T. Digital health interventions for healthy ageing: a qualitative user evaluation and ethical assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:1–10.

De Santis KK, Mergenthal L, Christianson L, Busskamp A, Vonstein C, Zeeb H. Digital Technologies for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in older people: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e43542.

Pan American Health Organization and International Telecommunication Union. The role of digital Technologies in Aging and Health. Washington, D.C.; 2023.

Cooper K, Schofield P, Smith BH, Klein S. PALS: peer support for community dwelling older people with chronic low back pain: a feasibility and acceptability study. Physiotherapy. 2020;106:154–62.

Terp R, Kayser L, Lindhardt T. Older patients’ competence, preferences, and attitudes toward digital technology use: explorative study. JMIR Hum Factors. 2021;8(2):e27005.

Fenge L-A, Melacca D, Lee S, Rosenorn-Lanng E. Older peoples’ preferences and challenges when using digital technology: a systematic review with particular reference to digital games. Int J Educ Ageing. 2019;5(1):61–78.

Airola E. Learning and use of eHealth among older adults living at home in rural and nonrural settings: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(12):e23804.

Svendsen MJ, Wood KW, Kyle J, Cooper K, Rasmussen CDN, Sandal LF, et al. Barriers and facilitators to patient uptake and utilisation of digital interventions for the self-management of low back pain: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e038800.

Geraghty AW, Roberts LC, Stanford R, Hill JC, Yoganantham D, Little P, et al. Exploring patients’ experiences of internet-based self-management support for low back pain in primary care. Pain Med. 2020;21(9):1806–17.

Belton JL, Slater H, Ravindran TS, Briggs AM. Harnessing People’s lived experience to strengthen health systems and support equitable musculoskeletal health care. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(4):162–71.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our search specialist Elisabet Hafstad for her expertise in developing and conducting the search for this synthesis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Norwegian Institute of Public Health (FHI) This synthesis was commissioned and funded by the WHO to contribute to a guidelines process. The lead authors (HA and CHH) discussed the synthesis objectives and inclusion criteria with the commissioner. HA and CHH independently conducted the synthesis and came to the findings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceptualised the synthesis and wrote the protocol. HA and CHH conducted the search, study selection, analysis, and decision on findings. AMB was not involved in data extraction or synthesis. AMB acted as a subject expert during the synthesis process and connecting the findings of the synthesis to the broader field. All authors were involved in drafting this manuscript.

Authors’ information

HA is an anthropologist and health systems research who has been working with qualitative evidence synthesis since 2013. She is a senior researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and an Associate convener with the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group.

CHH is a health systems researcher with a speciality within nutrition. She has been working with qualitative evidence synthesis since 2018. She is a senior advisor at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health where she specialises in conducting systematic reviews.

AMB is a consultant to the WHO, supporting the development of the WHO Guideline on chronic primary low back pain in adults. He is also a health systems and services researcher and practicing physiotherapist.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

HA and CHH declare that they have no competing interests. AMB declares he works as a consultant to the WHO.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy.

Additional file 2.

Machine learning plan.

Additional file 3.

Excluded full text studies with reason.

Additional file 4.

Evidence profile table.

Additional file 5.

Final adapted framework.

Additional file 6.

ENTREQ Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ames, H., Hestevik, C.H. & Briggs, A.M. Acceptability, values, and preferences of older people for chronic low back pain management; a qualitative evidence synthesis. BMC Geriatr 24, 24 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04608-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04608-4